“None of us is as smart as all of us” is a well-known quote by management consultant Kenneth Blanchard. It summarizes the intuitive and commonly held sentiment that teams are more intelligent and capable than individuals. Teams have more brainpower, knowledge, and experience. When confronted with a difficult decision, you want a team — not just one individual — to analyze, deliberate, and resolve the situation.

But is the superiority of team decision making a reality or a myth? Behavioral-psychology research suggests that the answer is not as simple as it may seem.

On This Page:

The Common-Knowledge Effect

Psychologists Garold Stasser and William Titus found that teams often do not live up to their decision-making potential. Instead of harnessing the members’ collective resources to make robust decisions, teams spend most of their time discussing the information they all already know and not enough time on uniquely held information, consequently engaging in poor decision making. This phenomenon hindering team decision making (just one problem among many, such as groupthink) has been consistently confirmed by psychology researchers over four decades.

Definition: The common-knowledge effect is a decision-making bias where teams overemphasize the information most team members understand instead of pursuing and incorporating the unique knowledge of team members.

Let’s walk through a scenario demonstrating how the common-knowledge effect can hamper your team’s decision making.

Scenario

Assume you’re a UX leader at a software company. You and your colleagues must decide on pursuing one of three possible projects, A, B, and C, next year. Because this is a strategic decision requiring cross-department coordination and sizable investment, each project has been extensively researched. Multiple facts are known about each project.

To construct this scenario, we used ChatGPT to generate plausible factual statements for each software project. The statements focused on engineering, product management, or user-experience topics. All statements could either be positive or negative. Positive statements suggested that a project would be advantageous, profitable, or beneficial to the organization. Negative statements suggested a project would be challenging, costly, or detrimental to the organization. As part of the statement-generating prompt, ChatGPT was instructed to use sentiment analysis to create statements that were roughly equivalent in the magnitude of their positivity or negativity. (For example, we wouldn’t want a statement like This project is expected to generate billions in revenue, as it would make choosing a project too easy.)

|

Statements |

Project A |

Project B |

Project C |

|

Positive |

4 |

7 |

4 |

|

Negative |

6 |

3 |

6 |

Based on this distribution of statements, it’s easy to determine that project B is the optimal choice: it has the most positive and the fewest negative statements compared to the other projects.

Individual Decision Making

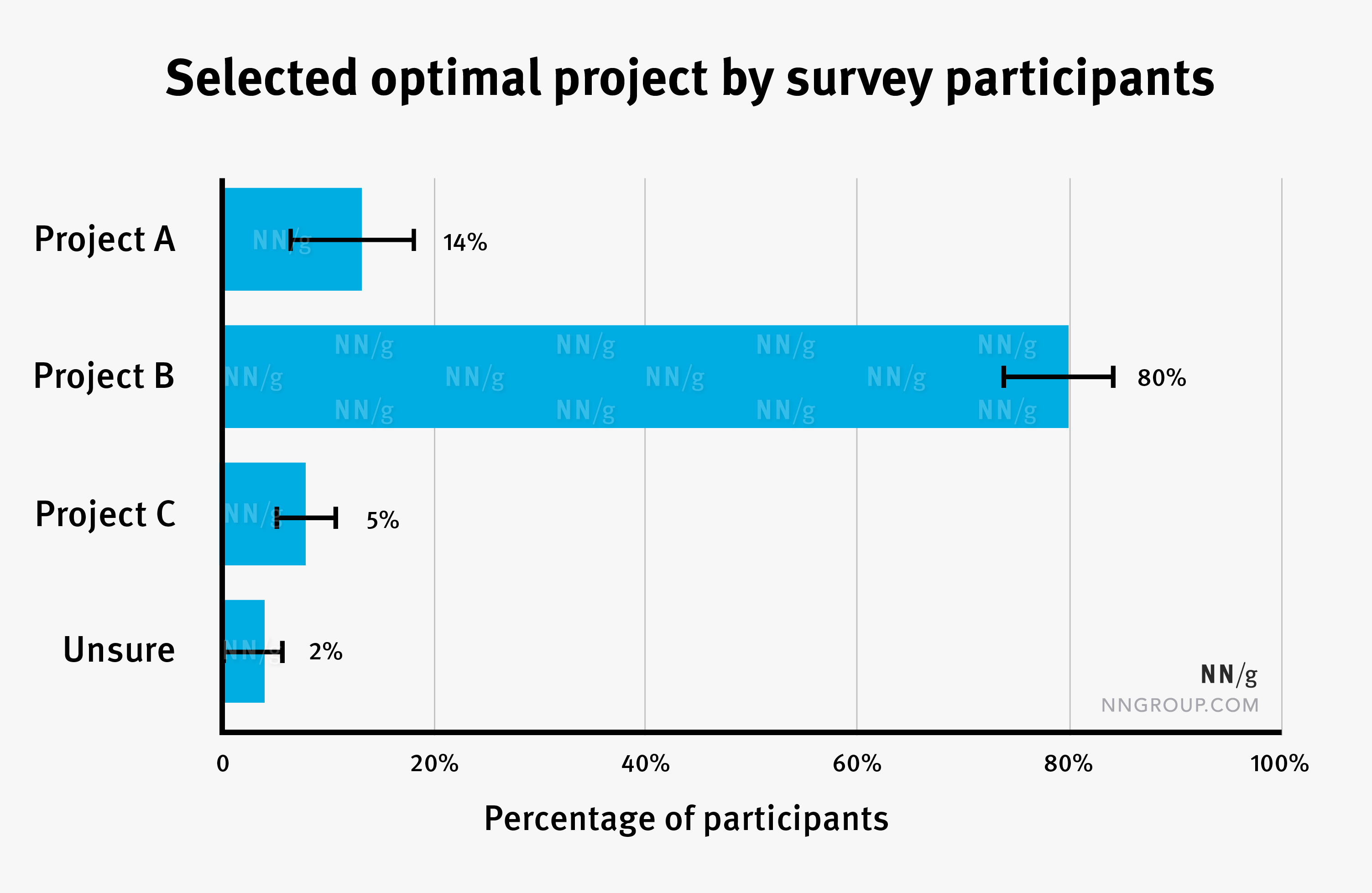

We then used this scenario in a digital survey with 307 participants in April 2023. A majority of participants were designers or UX researchers.

We presented the above scenario and gave participants 10 minutes to review all statements for each project. The survey tool required all participants to view the statements for 10 minutes before submitting their decision on which project to pursue to ensure a standardized time for evaluation. All statements were listed in randomized order under their respective project without indicating a statement’s positivity or negativity. We also informed participants that of the three available projects, one was objectively optimal compared to the others, and they should focus on determining this ideal solution based on the statements provided.

When presented with all available project statements, 80% of participants selected Project B as the recommended project, which was indeed the optimal choice. Of course, in the real world, we never have perfect and complete information regarding our decisions, but this feedback assures us that, if all these project statements are analyzed, then project B is generally seen as best.

Team Decision Making

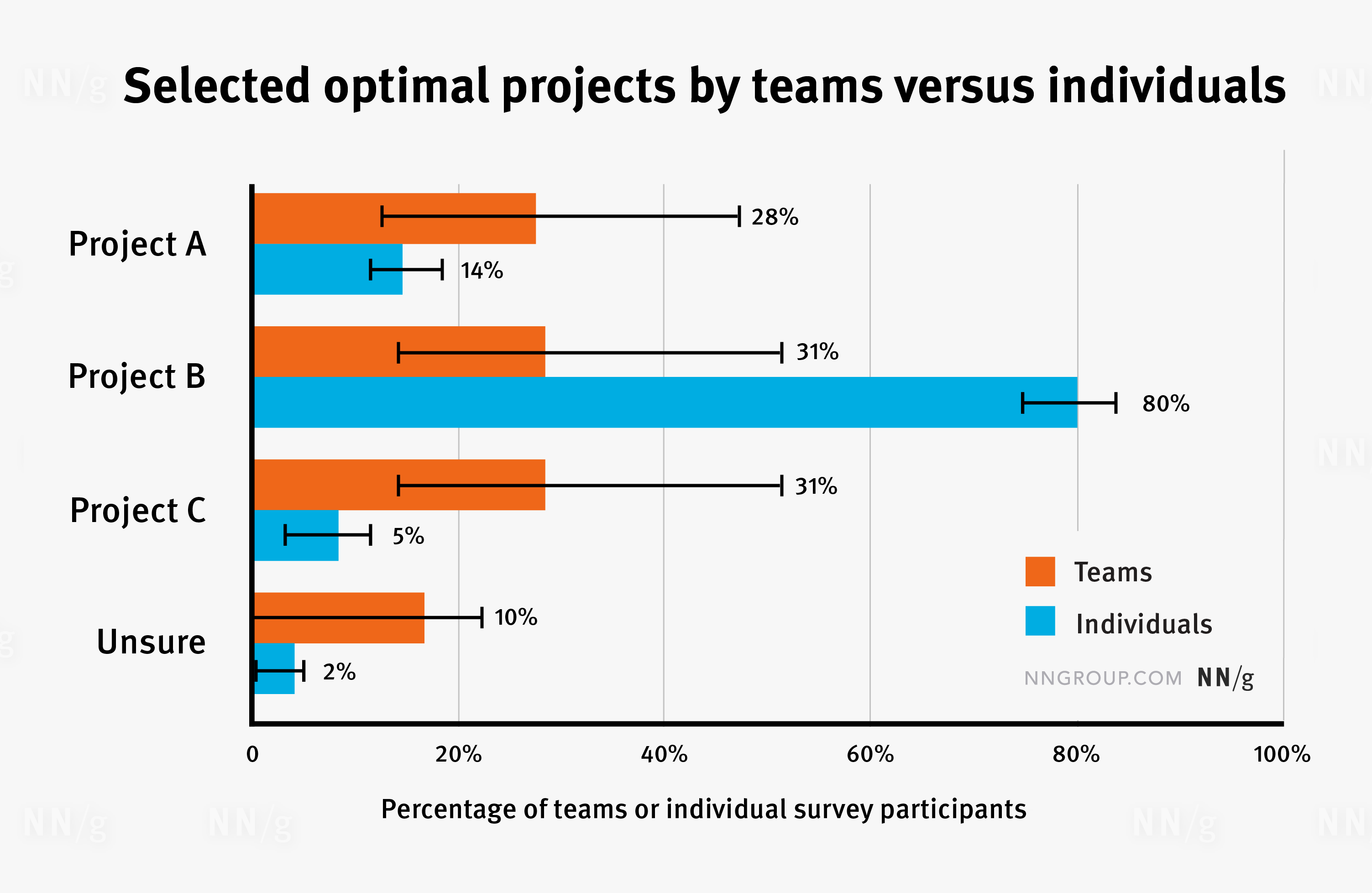

An interesting phenomenon happens when this scenario is given to teams. If each team member is provided with all project statements, then the team can match the decision-making effectiveness of an individual (which is about 80%). But what if information is not equally shared among all team members? Information asymmetry is prevalent in the UX workplace. Departments and their leaders have different domains of expertise, are measured on various metrics and goals, and may have personal agendas influencing what they divulge to others. In addition, the organization may be less proficient in acquiring new data through research, or its corporate culture may promote secrecy and discourage knowledge sharing.

Furthermore, team members often have preformed preferences that influence their high-stakes decision making. People evaluate what they know about a situation, are influenced by their motivations and biases (both conscious and unconscious), and form opinions before deliberating with others.

With this understanding, we presented participants in our Design Tradeoffs and UX Decision Making course the following adjusted scenario, that simulates a real-world, team-based decision-making process:

- Each team member was given a portion of the project statements. (All statements remained identical to those used in the individual decision-making survey.)

- Project statements were distributed unevenly:

- Projects A and C had all their positive statements shared with all team members. Their negative statements were divided between team members.

- Project B had all its negative statements shared with all team members. Most of its positive statements were divided between team members.

- Each team member was given time to review their project statements privately and decide which project is best. Team members could take personal notes and use them in their subsequent team deliberations.

- Afterward, team members got together and were given 10 minutes to share, discuss, and determine the best project.

If the team facilitates knowledge sharing and learns from each member’s unique information — as the ideal team decision-making process should go — it will likely identify and select project B as the optimal choice. However, if the team leans towards premature consensus building and commonly understood facts, it’ll probably select suboptimal projects A or C instead.

When we give this scenario in our Design Tradeoffs and UX Decision-Making course, the percentages vary from one course installment to the next, but the results are generally the same: most teams are unable to facilitate their decision-making discussion effectively. Teams select the optimal project at a significantly reduced rate compared to individuals.

Why Does the Common-Knowledge Effect Happen?

Decision-making is inherently complex, and involving more people makes it even more complicated. The mixture of individual traits, group dynamics, and social hierarchy can all perpetuate the common-knowledge effect when multiple people are involved. Communication expert Gwen Wittenbaum has developed a framework to categorize the many factors affecting the information sharing of groups:

Information Availability and Memory

- We are more likely to recall and discuss recent or memorable information.

- Commonly held information has more opportunities to be shared with the team since several team members possess it. Unique information depends on an individual sharing it.

- Once information is shared with a team, it tends to be repeated by others, which boosts its perceived credibility.

Preference Bias

- We are more likely to discuss information that aligns with our initial preferences or preconceived notions.

- Even when all information is shared with the group, we still process that information according to our initial preferences.

Social Comparison

- We seek social acceptance and avoid conflict with teammates. We tend to adopt the group’s prevailing view when evaluating information in unclear situations.

- Information familiar to multiple team members becomes socially validated and more likely to be repeated and affirmed.

Why the Common-Knowledge Effect Matters to UX

The common-knowledge effect has a real-world impact on UX professionals for several reasons:

- You are often making team decisions. Even for small-scale tactical decisions, UX needs collaboration with other departments to see their insights or designs implemented. Creating digital experiences demands teamwork.

- You are often outnumbered. UX professionals are usually fewer in number compared to other groups, such as developers. Consequently, unless UX knowledge is regularly distributed and socialized, such information is unique and not commonly understood by other team members.

- You are often an outsider. Especially in organizations with lower UX maturity, with new UX roles or departments, UX can be a “cognitively peripheral” group, meaning that it may lack knowledge known to other team members. Research by Susanne Abele and colleagues found that members who share more knowledge with other team members were “cognitively central” and seen as more credible and influential in discussions. Team members with mostly unique knowledge struggled to persuade their fellow team members successfully.

How to Mitigate the Common-Knowledge Effect

Here are some tips on how UX professionals can mitigate the common-knowledge effect in their group decision making:

- Promote psychological safety. Despite being a great learning opportunity, UX-research findings may disappoint or upset the organization’s status quo. Sharing this type of dissenting information is challenging if the environment feels unwelcoming. Leaders must model and normalize mutual respect and open communication with their teams.

- Be aware of role-power imbalance. Leaders who insert themselves into team decision making will distort information sharing; delegate exploring complex decisions to teams of equals.

- Deliberating in person isn’t superior to online. According to research by Simon Lam and John Schaubroeck, virtual teams are more likely to overcome the common-knowledge effect compared to face-to-face teams, perhaps due to easier access to notes and materials.

- Disregard past opinions. Strongly encourage colleagues (especially yourself) to put aside preconceived ideas about the best choice. This approach is quite difficult, but research by Torsten Reimer, Andrea Reimer, and Verlin B. Hinsz suggests that premature judgments ruin our decision-making capabilities. In their study, teams whose members avoided making hasty judgments before deliberating were likelier to overcome the common-knowledge effect and make optimal decisions.

- Unite around common goals. Because human nature is prone to factionalism, UX folks can expect cross-departmental rivalries. But a product team doesn’t necessarily succeed by reusing the most code, being the first to release a new product, or fully implementing a design with pixel-perfect precision. Remind team members of KPIs and goals relevant to all involved to disrupt siloed thinking and agendas that may inhibit information sharing.

- Remind team members of their individual expertise. Publicly recognize team members with domain expertise to coax the sharing of unique knowledge. For example, a developer is well-suited to knowing facts about potential technical complications.

- Warn against overconfidence bias. Remind team members that, although they possess expertise, our understanding of complex topics is often incomplete and oversimplified.

- Don’t rush to consensus. Never start a crucial decision-making meeting by polling, voting, or requesting opinions from participants (even anonymously). These activities reduce information sharing and processing and make it challenging to integrate new knowledge.

- Prioritize data gathering. Instruct team members to brainstorm before a deliberation meeting and come prepared to share their information immediately. Budget more time for this process when the consequences of failure are high.

- Visualize the data. Anyone who’s engaged a team with a prototype has experienced the power of getting people out of their heads and onto a common understanding that all can see (a valuable aspect of UX deliverables). Favor recognition over recall. Use whiteboards and write down all contributed information to ease the cognitive load.

- Mitigate social loafing. When team members withdraw from discussions, they stop contributing their unique knowledge. Direct questions to members exhibiting this behavior to reengage them.

- Involve others in UX research activities. One of the advantages of having colleagues participate in user research is that they gain first-hand knowledge. This tactic transforms UX research results from unique to common knowledge.

- Be cautious of using a devil’s advocate. A devil’s advocate is a team member assigned to critically review proposals to uncover problems or unrevealed opportunity costs. Research by Charles Schwenk and Richard Cosier suggests this tactic has mixed results. A devil’s advocate can improve critical thinking but also decrease team members’ desire to work together in the future.

Conclusion

As counterintuitive as it seems, increasing the number of people involved in a difficult decision will likely decrease decision-making quality. Whatever unique knowledge individuals could offer to deliberations often goes unshared or disregarded. When decision-making stakes are high, don’t let your valuable UX insights fall victim to the common-knowledge effect. Be a vigilant team facilitator to ensure that all of us are at least as smart as each of us.

References

Garold Stasser and William Titus. Pooling of unshared information in Group Decision making: Biased information sampling during discussion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 48, 6 (1985), 1467–1478. DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.48.6.1467

Susanne Abele, Garold Stasser, and Sandra Vaughan-Parsons. Information Sharing, Cognitive Centrality, and Influence Among Business Executives During Collective Choice. ERIM Report Series Reference No. ERS-2005-037-ORG, (2005).

Torsten Reimer, Andrea Reimer, and Verlin B. Hinsz. 2010. Naïve groups can solve the hidden-profile problem. Human Communication Research 36, 3 (2010), 443–467. DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2010.01383.x

Gwen M. Wittenbaum, Andrea B. Hollingshead, and Isabel C. Botero. 2004. From cooperative to motivated information sharing in groups: moving beyond the hidden profile paradigm. Communication Monographs 71, 3 (September 2004), 286–310. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/0363452042000299894

Charles R. Schwenk and Richard A. Cosier. 1993. Effects of Consensus and Devil’s Advocacy On Strategic Decision-Making. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 23, 2 (January 1993), 126–139. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1993.tb01056.x

Simon S. K. Lam and John Schaubroeck. 2000. Improving group decisions by better pooling information: A comparative advantage of group decision support systems. Journal of Applied Psychology 85, 4 (2000), 565–573. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.4.565